In a recent study conducted by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) it has been found that the Automatic emergency braking (AEB) systems fails to detect pedestrian well in the dark or at high speeds.

In all light conditions, crash rates for pedestrian crashes of all severities were 27 percent lower for vehicles equipped with pedestrian AEB than for unequipped vehicles, a new study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety found. Injury crash rates were 30 percent lower. However, when the researchers looked only at pedestrian crashes that occurred at night on roads without streetlights, there was no difference in crash risk for vehicles with and without pedestrian AEB.

“This is the first real-world study of pedestrian AEB to cover a broad range of manufacturers, and it proves the technology is eliminating crashes,” says Jessica Cicchino, IIHS vice president of research and the study’s author. “Unfortunately, it also shows these systems are much less effective in the dark, where three-quarters of fatal pedestrian crashes happen.”

Already, IIHS has spurred manufacturers to improve their front crash prevention systems and make pedestrian detection available on more vehicles by introducing ratings for pedestrian AEB. When IIHS made an advanced or superior rating for vehicle-to-pedestrian front crash prevention a requirement for the Top Safety Pick and Top Safety Pick+ awards in 2019, the technology was only available on 3 out of 5 vehicles the Institute tested, and only 1 in 5 earned the highest rating of superior. Two years later, pedestrian AEB is available on nearly 9 out of 10 model year 2021 vehicles, and nearly half of the systems tested earn superior ratings.

“The daylight test has helped drive the adoption of this technology,” says David Aylor, manager of active safety testing at IIHS. “But the goal of our ratings is always to address as many real-world injuries and fatalities as possible — and that means we need to test these systems at night.”

Impact of pedestrian AEB

Pedestrian crash deaths have risen 51 percent since 2009, and the 6,205 pedestrians killed in 2019 accounted for nearly a fifth of all traffic fatalities. That same year, around 76,000 more pedestrians sustained nonfatal injuries in crashes with motor vehicles.

Pedestrian AEB systems warn drivers when they’re at risk of hitting a pedestrian and apply the brakes if necessary to avoid or mitigate a crash. To determine how big an impact the technology is having, Cicchino looked at nearly 1,500 police-reported crashes involving a wide variety of 2017-2020 model-year vehicles from different manufacturers. Accounting for the quality of vehicle headlights as well as driver age, gender and other demographic factors, she compared pedestrian crash rates for identical vehicles with and without pedestrian AEB. Finally, she examined the impact of the technology by crash severity, light condition, speed limit, and whether the vehicle was turning.

Overall, pedestrian AEB was associated with a 27 percent reduction in pedestrian crash rates of all severities and a 30 percent reduction in injury crash rates. However, among the subset of nearly 650 crashes for which detailed information about the lighting conditions, speed limit and configuration of the crash was available, a more complex picture emerged.

Those more detailed results showed that pedestrian AEB reduced the odds of a pedestrian crash by 32 percent in the daylight and 33 percent in areas with artificial lighting during dawn, dusk and nighttime. But in unlighted areas, there was no difference in the odds of a nighttime pedestrian crash for vehicles with and without the crash avoidance technology.

Similarly, pedestrian AEB was associated with a 32 percent reduction in the odds of a pedestrian crash on roads with speed limits of 25 mph or less and a 34 percent reduction on roads with 30-35 mph limits, but no reduction at all on roads with speed limits of 50 mph or higher or when the vehicle was turning.

Night-time track tests

Recently, IIHS conducted a series of research tests to help design the planned nighttime pedestrian AEB evaluation. Those tests provide additional evidence that today’s pedestrian AEB systems don’t work as well in the dark as they do in daylight.

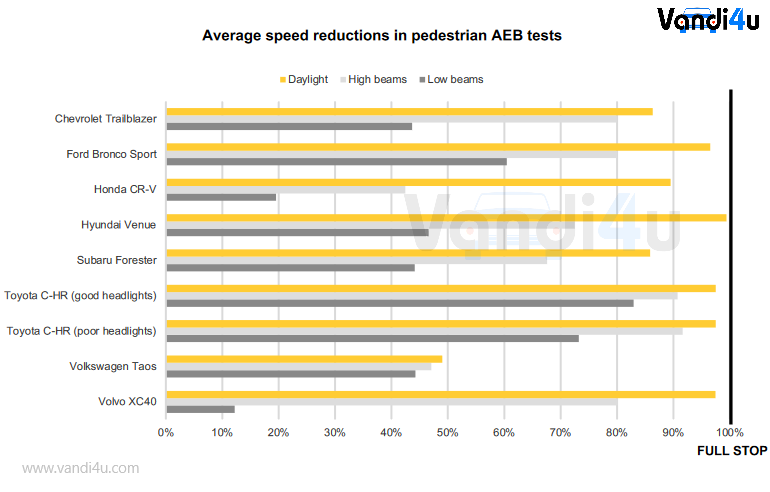

For the research tests, eight small SUVs made by eight different manufacturers were put through the standard vehicle-to-pedestrian evaluation in full darkness on the covered track at the IIHS Vehicle Research Center. Each vehicle was tested twice — first with their high-beam headlights on and then their low beams.

The test vehicles were a 2019 Subaru Forester, 2019 Volvo XC40, 2020 Honda CR-V, 2020 Hyundai Venue, 2021 Chevrolet Trailblazer, 2021 Ford Bronco Sport, 2021 Toyota C-HR and 2022 Volkswagen Taos.

The sample included vehicles whose AEB systems use a single camera, a dual camera, a single camera and radar, and radar only. It also included vehicles that earn superior, advanced and basic ratings in the Institute’s daylight vehicle-to-pedestrian front crash prevention evaluation, as well as vehicles equipped with good, acceptable and poor headlights.

Excluding the radar-only Taos, performance generally declined enough in the dark to knock vehicles from superior to advanced using their high beams and from superior to basic using their low beams, using the scoring system developed for the daytime ratings. But the benefits of radar varied in this small sample of vehicles.

As expected, the Taos achieved essentially the same results in the dark, since radar does not depend on light. However, it was also the worst performer in the daytime test. The best performers in the nighttime tests — the C-HR and Bronco Sport — both use a combination of camera and radar. The Forester and Trailblazer, the only vehicles with camera-only systems and no radar, achieved similar nighttime results to three other vehicles with camera-and-radar systems, the CR-V, XC40 and Venue.

“The better-performing systems are too new to be included in our study of real-world crashes,” Aylor says, “This may indicate that some manufacturers are already improving the nighttime performance of their pedestrian AEB systems.”

The research tests did not show a clear association between good headlights and stellar nighttime scores, either. On average, vehicles with good and acceptable headlights showed similar declines in performance in the dark, compared with their daytime results. The two worst performers in the low-beam test, the CR-V and XC40, both had good-rated headlights. And the C-HR, which was tested with both good and poor headlights, outperformed all the others using its low beams, even when equipped with poor headlights.